[Editor's Note: UPDATE: The following text has been edited slightly since publication to clarify some quoted comments.]

Any environmentalist or conservationist or any person of logic would agree that biodiversity is an integral part of climate change. Biodiversity loss, its mitigation and adaptation are linked to adaptation and mitigation strategies for climate change. We cannot tackle biodiversity loss without tackling climate change nor can we address climate change without addressing biodiversity loss. This is why COP 15, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) conference, held last December in Montreal, is important relative to COP 27, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conference, held last November in Egypt.

Indigenous communities are at the forefront -- they face the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss first and most. They are the frontline communities who are becoming the voice of protest against the misrecognition of their contribution and the discrediting of their knowledge as non-science. Indigenous groups were present and outspoken at both of these global conventions.

Indigenous peoples’ knowledge and their approach in safeguarding ecosystems is increasingly recognized at the international level, including COP 27 and the recently concluded COP 15. The voices of Indigenous people, with their wealth of local knowledge acquired and preserved over centuries, were present during COP 27 in the form of protest against neglect of Indigenous knowledge and in COP 15 as the main voice championing change. Their participation in policy, debate and a broader agenda setting has been recognized only in recent years. It was only as recent as in the 23rd UNFCCC COP (2018) that Local Communities and Indigenous peoples were operationalized as an entity that would engage with other stakeholders through their valuable knowledge in the fight against climate change and its impacts.

It all started in 1988 when the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) convened an Ad Hoc Working Group on Biological Diversity to explore the need for an international convention on biological diversity, resulting in the formation of the Ad Hoc Working Group of Technical and Legal experts in May 1989. The group was tasked with the preparation of an international legal instrument for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity (Scott 2014).

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) came into force in 1992 during the Earth Summit at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and entered into force at the end of 1993. The recognition of Indigenous peoples and their contribution to biological diversity protection was recognized in 1998 when Article 8(j) was enshrined into the preamble of the CBD. In 2000, the COP adopted a programme of work to implement the commitments of Article 8(j) of the Convention in order to enhance the role and involvement of Indigenous peoples and local communities.

CBD is one of the many multilateral agreements/frameworks that have been constituted in the short history of environmentalism and climate change adaptation and mitigation. The need for such multilateral agreements has arisen for two reasons. First, the problem sets are unique and affect different geographies disproportionately. Second, and more importantly, the parties (a misnomer that includes nations and territories who often are in conflict with each other) cannot agree on a democratic set of rules and regulations despite being "parties." Given the amount of resources exhausted over years of such meetings across various cities, they should ideally be referred to as Herd of Detractors (HoD).

CBD was one of the three conventions adopted at the Rio Summit (1992) held in Brazil. The other two landmark conventions were the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) and the Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD). COP 15 (2022) was important because the Parties were to review the Strategic Biodiversity Plan (2011-2020) including the Aichi targets that were set in the 10th meeting of COP to the CBD in Japan in 2010. The Aichi Biodiversity targets were meant to tackle biodiversity losses -- a goal which is very much linked to the Paris agreement target of limiting global temperature to 1.50C. However, there is a disconnect between the biodiversity targets and the climate change targets, both of which have been ratified by the same member Parties (with some exceptions). Nonetheless, given the failure to achieve the Aichi targets, this COP 15 was crucial to finalize and adopt the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which aims to address biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems and protect Indigenous rights and which would subsume previous Strategic Plans.

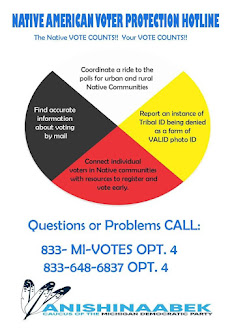

I spoke to Carley Dove-McFalls, a fierce climate justice activist and a McGill University alumna who participated in COP15 last December. Carley participated in a panel discussion along with representatives of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, the Anishinaabek Nation and other Great Lakes Indigenous water protectors on the issue of protecting the Great Lakes from the threat of Line 5, a 645-mile long oil pipeline that carries petroleum from western Canada to eastern Canada.

"I’m sceptical about the efficacy of both COP 15 and COP 27," Dove-McFalls said. "The bureaucracy and the scale of these meetings are simply not conducive to the changes that we need, as much proof has shown. It also seems quite ridiculous that there is such a stark division between the conferences on biodiversity and climate change as they cannot be dissociated. In general, these conferences simply reproduce the broken and violent (political, social, economic) systems that we operate in because the decision-makers are corrupt and generally prioritize lining their country’s pockets (on the short-term). These conferences are therefore not 'radical' enough to do anything."

Despite the efforts of Indigenous activists and water protectors at COP15, people in power only paid lip service to reconciling environmental injustice faced by Indigenous people with forward looking measures. The Indigenous community is incredibly frustrated because of the utter lack of clear and efficient changes needed.

During COP 15 in Montreal, Indigenous communities protest against Enbridge, the company owning Line 5. (Photo © and courtesy Rebecca Kemble**)Many Indigenous communities were present at COP 15 to protest against Enbridge and their complete neglect of wildlife and environmental regulations. Constructed in 1953, Line 5 carries 23 million gallons of oil daily underneath Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, which meet at the Straits of Mackinac. Since 1968 there have been at least 33 oil spills from the Line 5 pipelines that have severely damaged the flora and fauna around that area. According to research by the University of Michigan, any more oil spills now would threaten 700 miles of shoreline with contamination. This would affect the Great Lakes and the entire ecosystem supported by it. Just one example of a species whose habitat is threatened by a potential oil spill is the Piping plover -- an endangered species of shorebird found along the shorelines of the Great Lakes.

The experience of Indigenous communities who were present at COP 15 and at COP 27 brings out the disconnect between biodiversity targets and climate change targets. COP 27 and COP 15 do not speak to each other -- neither in terms of the output produced, nor through the spokespersons who represent the Parties at the two conferences.

Pipeline protest banner in Montreal. Indigenous water protectors have also been opposing Enbridge’s Line 3 for several years, and some have been arrested by law enforcement paid by Enbridge, including Honor the Earth leader Winona LaDuke. (Photo © and courtesy Rebecca Kemble**)According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, climate change will be the most significant driver of biodiversity loss by the end of the century. Climate change has already forced biodiversity to adapt either through shifting habitat, changing life cycles, or the development of new physical traits. Ecosystem based services that conserve natural terrestrial, freshwater and aquatic ecosystems are essential not only to meet the goals of the GBF, but also to meet the scientifically determined targets under UNFCCC. Understanding this phenomenon requires acknowledging Ecological Knowledge (EK), which includes Indigenous knowledge, as climate science -- and integrating that knowledge in policy making. However, little attention has been paid to the history of local knowledge present in Indigenous communities.

The use of EK has been slow and reductive in nature. The alternative pathway is to treat EK as a process, rather than as a source of information only. Accrediting the tribes and communities as environmental stewards and using their EK for climate change solutions is one important element of integrating the knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystem services into an overall Climate Change Adaptation strategy in order to make that strategy cost-effective; capable of generating social, economic, and cultural co-benefits; and capable of contributing to the conservation of biodiversity.

Editor's Notes:

* Guest author Aritra Chakrabarty is a PhD Research Scholar in Environment and Energy Policy at Michigan Tech University.

** Thanks to Rebecca Kemble, journalist for the Wisconsin Citizens Media Cooperative (WCMC) for her photos of water protectors demonstrating at COP 15 in Montreal. CLICK HERE for her video, now on YouTube, with more photos. WCMC journalist and Keweenaw Now guest author Barbara With assisted with technical assembly of the video content.

No comments:

Post a Comment