Western Upper Peninsula wolf. Note the collar and red ear tag in right ear indicating she was collared in Michigan. Click on photo for larger version.

In order to understand the latest updated Wolf Management Plan for Michigan, you may wish to review these Fast Facts:

- Federal protections, under the Endangered Species Act, were restored on February 10, 2022, for wolves in most of the US, including Michigan. Wolves in those states covered by the court order cannot be killed for any reason except defense of human life.

- In 2011, wolves in Montana, Idaho, Washington, Oregon and Utah lost their federal protections when a rider was attached to a "must-pass" federal budget bill. However, due to the egregious hunting and trapping practices in the Northern Rockies, a formal petition was filed by many conservation groups, including the National Wolfwatcher Coalition, to restore protections. A decision by US Fish and Wildlife Services is expected soon.

- The Michigan wolf population has remained stable for more than 12 years -- between 600 and 700 wolves. No wolves have been detected in the Lower Peninsula.

- Michigan’s UP has about 1,000 working farms, with 50,000 head of cattle. In 2022, only three farms experienced a conflict with wolves and only one farm experienced more than one event. Six calves were killed.

- Producers were reimbursed the fair market value for those animals killed as determined by the Michigan Department of Agriculture. Total amount paid was $3357.

- The low number of conflicts is consistent with prior years with only a handful of farms experiencing a conflict.

- Wolf-Dog conflicts are also low and consistently involve hunting dogs in pursuit of game such as bear, bobcat and hare.

- Upon delisting, livestock producers and dog owners can use lethal control if a wolf is "in the act" of attacking their animals; livestock producers can also be issued permits to use licensed hunters to kill wolves at chronic farms.

- Weather -- not wolves -- has the greatest impact on deer populations. Research shows that in the UP, nearly 70 percent of the wolf predations of adult does occurred in the late winter and spring months when body condition of deer was at its poorest. Further investigation into the body condition of adult does killed by wolves in the high snowfall zone found that nearly half (43 percent) were in extremely poor nutritional condition and likely would not have survived the winter even if they were not preyed upon.

- Before a wolf hunting and trapping season can take place, wolves need to be federally delisted. Then, DNR must engage in tribal consultations and consider input from stakeholders, department biologists, and the general public. Ultimately, the Natural Resources Commission will decide whether a hunting/trapping season will occur.

2022 Wolf Management Plan Update

Having served on the council for developing the guiding principles for the 2008 and 2015 plan updates, I understand what must be considered in a wolf management plan. Do wolves even need to be managed? There are different interpretations of what it means to "manage" wolves. There are competing values. Some believe the only good wolf is a dead one; others believe no wolf should be killed for any reason. Some question the ethics of collaring wolves. Fortunately, those extremes represent a very small minority.

What role should politics, lawsuits and the media play?

We learn more and more about wolves as evidenced by the more than 100 new scientific citations referenced in this updated plan. There is still so much more to learn. GPS collars and other technology have given us insight into pack dynamics, territory size, dispersal and mortality.

There is a role playing exercise I do with high school students with each team studying the position of a different stakeholder -- including the farmer who lost livestock to wolves, the hunter, the biologist, the politician, the Native American, the "protectionist," etc. Then a stuffed wolf is placed on a ring with cords attached to it while each student holds a piece of cord. They are tasked with lifting the wolf and walking with it and balancing the wolf and ring on a ball which moves. If one side pulls too hard, the wolf falls.

In this role playing exercise students learn how stakeholders need to work together to balance wolf management. (Photo courtesy Nancy Warren)Wolf management is a balancing act. Michigan wolves do not live in isolation. They do not understand state boundaries. We all need to work together for the wolf to survive and thrive in Michigan and elsewhere.

I believe the updated 2022 Michigan Wolf Management Plan, which was recently signed, accomplishes that goal.

Consistent with the 2008 and 2015 plans, the update provides guiding principles for wolf management and utilizes the most current biological and social science complied in the White Paper "Review of Social and Biological Science Relevant to Wolf Management in Michigan."

The four goals remain the same as described in the earlier plans:

• Maintain a viable population

• Facilitate wolf-related benefits

• Minimize wolf-related conflicts

• Conduct science-based and socially responsible management.

Also unchanged, the update does not identify a target population size, nor does it establish an upper limit for the number of wolves in Michigan.

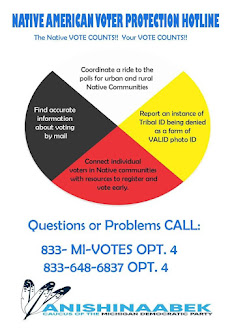

The plan also recognizes the cultural and religious values regarding wolves important to many Native Americans.

In general, statewide, public attitudes towards wolves have improved since the 2006 Survey.

The present Wolf Management Plan indicates the estimated percentage of people who desire a reduced wolf population is 24.0 percent while 49.9 percent desire an increase.

Majority of respondents do not support killing wolves in the event of wolves killing a pet, hunting dog or livestock; only 35 percent support lethal control to address predation on livestock, even less for hunting dogs and pets.

Statewide, less than half support a wolf hunting season (down from the 2015 survey). 70.2 percent of the general public strongly or moderately agreed that wolves are an important part of ecosystems. 80.2 percent strongly, moderately, or somewhat agree that wolves have an inherent right to exist. 49.9 percent desire an increase in the wolf population (24 percent prefer fewer). Support for compensation for livestock producers declined, only 48.5 percent indicated it was somewhat, moderately, or highly acceptable to use tax dollars for compensation (2015, 58 percent).

49.2 percent of state residents support and 30.4 percent oppose a legal, recreational hunting season for wolves, if biologists and the DNR believed the wolf population could sustain it.

2022 Plan Highlights

The Plan places a strong emphasis on the need for education and stresses the importance of non-lethal measures to resolve wolf conflicts.

It states, "To the extent non-lethal methods are effective at eliminating or minimizing depredation problems, lethal control of wolves will not be necessary. However, when such practices prove to be ineffective, are not expected to be effective, or are infeasible, lethal control may be necessary to prevent problems.

"Lethal control will be a management option in situations where loss of livestock has been documented or where a wolf is in the act of depredating livestock; it will not be used as a preventative measure in areas where livestock depredation has not yet occurred."

Some groups, lawmakers and even members of the Natural Resources Commission have often incorrectly interpreted the definition of a "viable" population of wolves, even though the prior plans clearly stated 200 wolves is not a target population size. Therefore, the updated plan further defines a viable population by explaining wolves are "an integral part of the natural resources of the State and are a component of naturally functioning Michigan ecosystems. In the context of the DNR’s mission and its implicit public trust responsibilities for the State’s wildlife, natural communities and ecosystems, the maintenance of a viable wolf population is an appropriate and necessary goal."

The Plan does not oppose or support a wolf hunting season. Rather, it addresses under what circumstances a hunt may take place for the purpose of reducing conflicts versus a recreational hunt.

For addressing conflicts through the use of hunters and trappers, the plan states, "If it is determined that the number of conflicts are correlated to wolf abundance, or the spatial extent of the conflicts indicate it involves multiple pack territories, it may warrant the consideration of reducing wolf numbers in areas that span multiple pack territories to reduce the risk of future conflicts. Such consideration could be necessary if a high density of wolves in an area, rather than the behavior of individual wolves, is determined to be responsible for problems that could not otherwise be addressed through non-lethal or individually directed lethal method." Further, it explains, "There is scientific uncertainty relative to the use of wolf harvest as a conflict management tool because most wildlife managers do not have experience with this approach for wolves."

When considering a wolf hunting / trapping season for recreational purposes, the DNR is committed to evaluating the biological effects of a season and public attitudes. The plan states, "If biologically sustainable, legally feasible, and socially responsible, develop recommendations to the NRC to offer opportunities for the public to harvest wolves for recreational purposes."

To address ecological, social, and regulatory shifts in a timely manner, the DNR will review and update this plan at 10-year intervals.

The wolf management plan is 74 pages (plus appendices and cited references). I highlighted just a few of the most controversial aspects of wolf management. If you have any questions, do not hesitate to contact me at nancy@wolfwatcher.org

Editor's Note: For more information and news from the National Wolfwatcher Coalition, visit their Web site: https://wolfwatcher.org/

.jpg)